[ad_1]

DISTANT PAST

Once upon a time there were classes in art, music and gym from Kindergarten through senior year in high school. Budget cuts, oversized classes and teaching to standardized test scores rather than comprehension and life skills have all taken an axe to these lifelines.

Mr Greaney was my gym teacher for those seven years of elementary school. He was a tall man with a deep voice and most of the year he wore a navy blue warmup suit, with white racing stripes. No matter your age or size, birthdays meant that you ended up over his knee with the class counting out loud as he gave you a gentle number of swats on your bottom equivalent to your age— and one for good measure! Jesus, Joseph and Mary, it’s like I’m telling a science fiction story for the resemblance between those moments and the politically correct, touch-phobic, probiety of the present.

Nobody messed with Mr Greaney. I don’t care if you thought you were a tough guy from the slums of Hartford, you were no match for him, and you knew it. Period.

Junior high school was a different scene, but our teacher was another physically fit and generally cool cat name Mr Steiner. He had black wavy hair and a mustache. He was perpetually relaxed, and had really good attention, meaning that when he was talking to you, you had him.

How many of us were vulnerable to the attention of adults when we were kids? I had been missing my dad since my parents divorced. My stepfather and I were locked in a battle of wills, and I ached for a father figure in my life who could help me find my way and love me with all of my faults. This is rich territory for pedophiles, and they were there in the shadows for sure. A narrow escape from one such predator is a topic for another day. It was both my good fortune, and painful dilemna, that Mr Steiner was a kind man who cared about his students in general, and me in particular.

Coach called the boys Chief, or Rocky, or some other name which he probably called hundreds, if not thousands, of other boys during his career. He called me, and only me, Moose. I chose to hear his designation as a sign of his respect and affection for me.

My best friend in junior high and freshman year of high school was Bill. He was a good student: big, strong, and willful. We both lived in households where alcohol influenced our family dynamics; still overflowing in mine, chicken scratching to maintain sobriety in his. In our circle of friends were other boys like Bob and Kevin who were physically strong and intellectually gifted. When Billy decided to join Bob and Kevin, on the freshman wrestling team, he persuaded me to sign up too. Mr Steiner just happened to be the high school wrestling coach.

The first weeks of wrestling practice are still pretty clear in my mind. The sheer physicality of it, the burning lungs, weary muscles, omipresent smell of adolescent sweat, and getting pounded on the mat time after time after time. As I’ve written before, I have plenty of experience with losing, but this took it to another level. After each practic, I remember the dim light of the locker room and the smell of Mennen SpeedStick. I would catch the late bus with just a few others, headed home in the dark, with a quarter mile walk home at the end of the bus ride. Once home I would scarf down dinner and then hit the books, every single weeknight.

About three or four weeks in, I decided I’d had enough. I was old enough to know what hard was, and this was beyond hard. It was like when you’re a little kid learning to walk and you faceplant on the sidewalk, except it keeps happening over and over. Sitting in Mr Steiner’s office and telling him that I was quitting was painful. I yearned for his approval. He wasn’t unkind, but in a way that made it harder. He said “Moose, I think you were doing well, that you could be good, if you stuck with it. I’m disappointed, and just afraid that quitting the team will become a pattern in your life. We learn persistence early.” Oooof!

Right in the solar plexus.

A few months later I was moving in with my adoptive paternal grandparents. I began to have chest pain and shortness of breath. It felt like I had an elephant sitting on my chest. Years later, my dad confided to me that my Pop pop had called him wondering if I was reacting to the stress of the recent upheaval in my life, and perhaps I was a bit of a hypochondriac. We went to my new pediatrician, he referred me to a sharp pediatric cardiologist, who quickly diagnosed me with idiopathic subaortic stenosis, which later became known as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or HCM. He quickly arranged for an evaluation at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, MD, the closest research center with significant experience in surgical intervention for HCM. This became the first of many trips Pop pop and I made together from our village of Parkerford, PA to the vast campus of the NIH. After a cardiac catheterization, surgery was recommended, and a week later I was on the operating table.

HCM is the number one cause of sudden cardiac death in young athletes, or at least before the pandemic it was. Over the years I can count three families connected to mine who have lost a son or daughter to undiagnosed HCM, all in their early 20s. Even in my teens, I quickly connected the dots, and understood that if I hadn’t gone against my aching need for the approval of Mr Steiner, I probably would have died on the wrestling mat. It really was too hard, and somehow I knew it.

RECENT PAST

Because I wasn’t able to participate in organized sports, or even regular gym class after my surgery, I was assigned to the Breakfast Club version of gym in high school with Mr Ronald Pearson, also known as Mr P. He was the Athletic Trainer for all of the sports teams, and had a group of students who volunteered as assistants. After a stint as a statistician for our champion football team, I became an assistant athletic trainer, and enjoyed traveling not only with the football team, but also boy’s basketball and the girl’s lacrosse team.

When I trundled off to Susquehanna University to study business economics, I had a work-study job as an athletic trainer before classes had even started. It was skilled and satisfying work with all the athletes, traveling with the football, men’s basketball, and women’s field hockey teams. Oddly, it had nothing to do with my chosen field of study, and everything to do with what would become my calling a decade later.

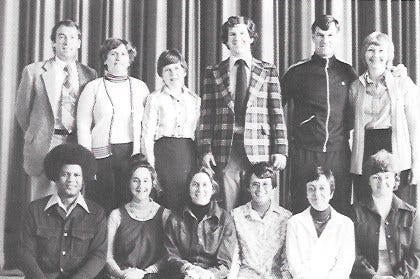

Connie Delbaugh was the golden haired beauty who coached field hockey, and was romantically involved with Don Harnum, the handsome Director of Athletics and men’s basketball coach. I loved working with the field hockey team, and would hang with them after practice and games. They were some seriously tough and sexy women, a few of them heavy drinkers who could get pretty rough. Nancy, #27 in the photo, was the recipient of my daily treatment for shin splints in the training room. We became close friends, and after a while longer, romantically involved.

Coach Delbaugh was very kind to me and made me feel welcome and appreciated for my efforts. This is a small but poignant example. Once we arrived early for an away game and the gate was locked, with nobody around. I volunteered to climb over the fence and unlock it from inside, managing to tear my pants in the process. She took them home and repaired them by hand. Good golly.

PRESENT

In the first and second case studies I have presented at the last two FLCCC Alliance conferences, and the case study in my substack last week, pacing has been the Achilles heel of each patient. It isn’t for nothing that Dr Walskog of REACT-19 presents the number one consensus recommendation of vaccine-injured as pacing. Not only is that true, but also that Physical Therapy is more likely to hurt patients with post-acute sequelae of COVID (PASC) and vaccine injury than to help them.

It has been with trepidation that I have enouraged some of my patients to explore Live02 as a tool to heal their enodthelium, decrease the pathological basis of their microclotting, and get back to a higher level of physical activity. The pre-pandemic use of Live02 incorporated extended periods of hypoxia (low oxygen) to cause vasodilation before then flooding the person with 100% oxygen while engaging in aerobic activity.

Our first patient to try this went to a studio in Baltimore, MD, felt great while doing Live02 with periods of hypoxia and increased resistance, for twenty minutes right out of the gate. Then he was down mentally, emotionally and physically for at least a week. The therapy harmed him.

Trying to learn from this initial experience, I counseled patients to avoid the hypoxic setting. A second patient went to a Live02 trainer, was run through a training session with periods of increased resistance and no hypoxia, felt okay during the session, and then experienced a dramatic decline in his status within tweny four hours. He developed dyspnea, chest pain, near syncope, and severe POTS symptoms, with a sharp escalation in his tinnitus. The effect was to set him back months in his clinical progress.

Still gathering information and trying to avoid any harm to other patients, I wrote out a short, very simple and firmly worded plan of care for patients who wished to try Live02. No hypoxia for at least two weeks, AND no increase in resistance. 100% 02. Slowly increase the time period of Live02 from three minutes (yes, only three minutes) the first session, to five the second, seven the third, nine the fourth, etc. Two patients improvised and incorporated near infrared sauna (NIR) for about forty five minutes prior to their Live02 sessions, took things slowly, avoided hypoxia and resistance, and have done very, very well.

The successes and lessons learned were communicated to other patients. Then last week I had a report from a patient who went to two sessions. Despite my instructions, the patient was assured by the trainer that he had helped many people with PASC and vaccine injury “go from bedbound to running marathons.” He put my patient on a treadmill with resistance, and ran him for 1.5 miles or > 20 minutes on the first day. The patient felt good during the sessions, but experienced an increase in his internal vibrations, dyspnea, and fatigue over the two days following each episode, coming back up to baseline.

I wasn’t very happy. I think that what is more dangerous than a trainer or practitioner who doesn’t know what he/she is doing, is one who is confident that he/she knows what he/she is doing, but is actively harming patients. The simplest way I can explain this is that pre-pandemic expertise expired around November 2019, and our bodies behave differently now, posing many challenges and mysteries to the individuals and practitioners trying to help them recover. We have a study in which muscle biopsies of both control and PASC patients pre- and post-exertion showed actual muscle necrosis and amyloid protein deposits in the tissue of the PASC patients. Going too far, too fast, is going to harm people.

My plan is to write a letter to the folks who manufacture and sell the Live02 setups, but they don’t supervise or control the people who purchase their equipment. I’m going to share this letter with my patients, and ask them to present it to the trainer they encounter when they book a Live02 session. I have low expectations that the trainers will pay it any heed. In the meantime, please beware of the Live02 trainers who claim to be helping hundreds of patients return to their marathon running capacties. That isn’t what I’ve seen in practice, and I think we need to make adaptations for the bodies we live in today.

P.S. Before I graduated from Susquehanna University, one of my closest friends presented me with a mix tape titled “Favorite songs for the men in my life.” It included Ode to a Gym Teacher by Meg Christian.

[ad_2]

Source link