[ad_1]

PROLOGUE

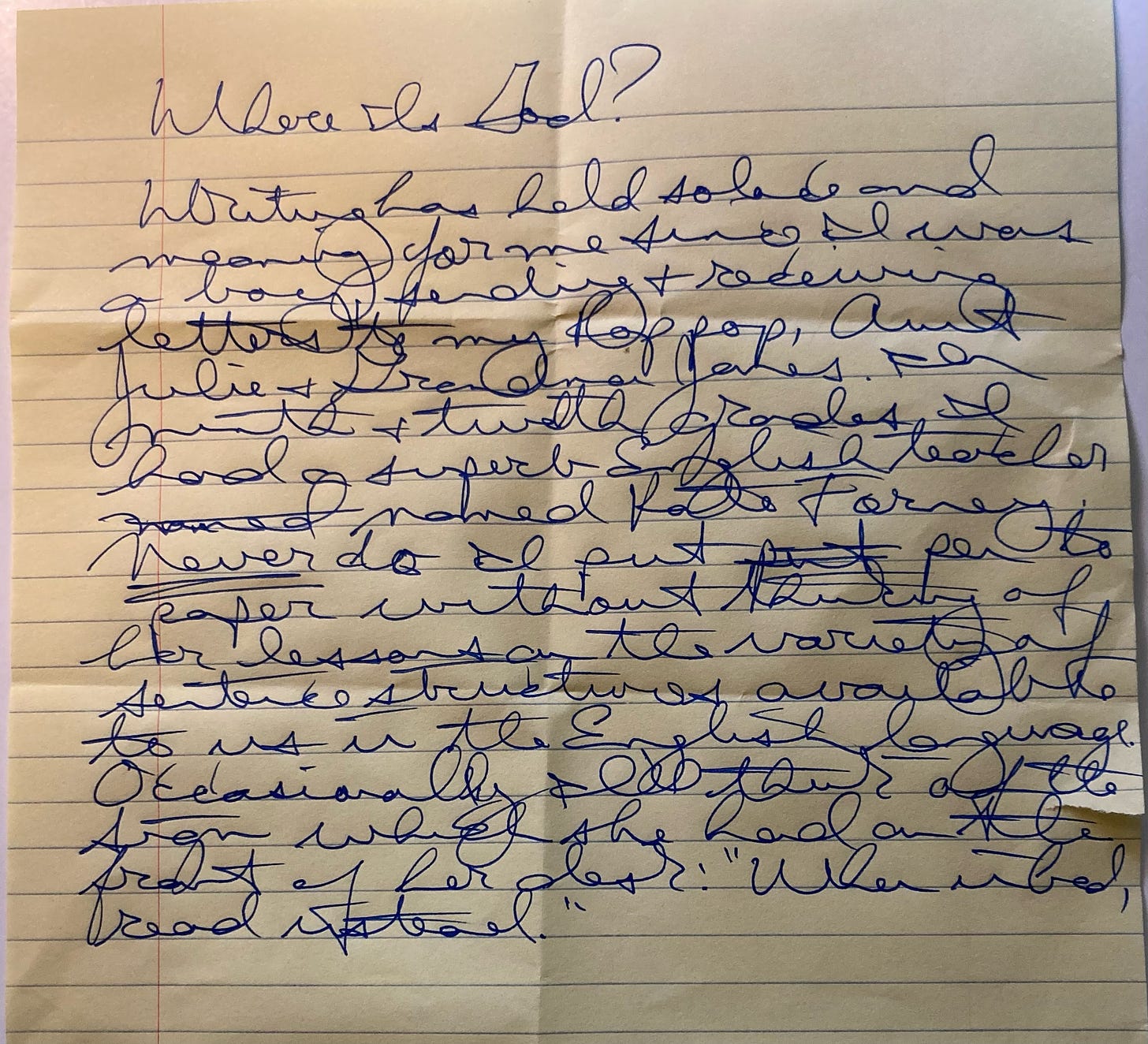

Writing has held solace and meaning for me since I was a boy, sending and receiving letters to my Pop pop, Aunt Julie and Grandma Jones. In ninth and twelfth grades I had a superb English teacher named Kate Forney. Never do I put pen to paper without thinking of her lessons on the variety of sentence structures available to us in the English language. Occasionally I’ll think of the sign which she had on the front of her desk: “When in bed, read instead.”

Powerfully written letters have helped me beat adversaries in the realms of legal challenges, financial missteps, unionizing struggles, human resource quagmires, and healthcare revolution. They have also helped me woo my beloved wife and make amends for thoughtless acts and spoken words.

If I had my druthers, I would write this Substack on paper, in cursive, and blue ink. This immediate act of writing gives me joy, and makes my right middle finger sore just below the distal interphalangeal joint. Alas, most of you wouldn’t be able to understand what I wrote, because my handwriting, which was never penmanship worthy of Catholic school standards, has not improved with age.

It was with surprise and delight that I received an invitation from Jenna McCarthy to submit up to three essays for inclusion in her book Yankee Doodle Soup. The material is wide-ranging, with a Covidian theme, and generally uplifting. If you feel inspired to buy a copy, for yourself or as a gift to another, please use the code MARSLAND to send some royalties my way.

Below is one of the essays which was accepted for Jenna’s book. I’m still wrestling with how to reconcile my spiritual path with organized religion at a time when the communities with which we might worship may still be slow to acknowledge the dark underbelly of the pandemic, and the physical risks which we take with our attendance.

DISTANT PAST, RECENT PAST, AND PRESENT

My religious experience as a child was all over the map. The first church I attended with my family was a white clapboard Congregationalist in New England. It was open and sunny, but very plain on the inside. As children we were permitted to attend the first 15 minutes, and then were dismissed to Sunday school. For several years, I attended a Lutheran Summer camp. I became a choir boy in an Episcopal church, the same denomination in which I was confirmed. One summer I spent a week going to a Bible camp led by our Evangelical neighbor. As a teenager, I began attending Quaker meetings at the invitation of my best friend’s parents.

Out of all of those experiences, I think that I felt most connected to God in music and in nature. As much as I have embraced Quakerism, I miss the hymns and the exquisite liturgical music of composers such as Handel, Bacon, and Mozart. Just thinking of The Doxology stirs my soul, the enormous pipe organ belting out the low rumbling tones and signaling the end of a service. We all knew to sing, “Praise God, from whom all blessings flow. Praise God, all creatures here below.”

After college, I volunteered for a year in the Brethren Volunteer Service. I worked at a Catholic Worker House, which ran a soup line and a homeless shelter for families in Texas, then at a very rural retreat center in Pennsylvania. Those were very rich years in my life, with an ongoing exposure to a wide range of practice, including working with DignityUSA (a nonprofit advocacy group for LGBTQ+ Catholics), and witnessing the quiet demonstration of faith working alongside men in their 70s and 80s as we cleared land to build a new retreat center.

My departure from the volunteer service and return to Philadelphia marked the beginning of a long dry spell in my relationship with religious practice and faith. Although Philadelphia has many lovely green spaces, I never felt that I could let my guard down for fear of being accosted or attacked. This wasn’t a figment of my imagination as during the decade that my wife and I lived in Philadelphia she was mugged, a store I was working in was held up at gunpoint, we interrupted a rape, and our neighbor was the victim of a drive-by shooting. I witnessed the inequality and suffering from an unjust economic system, and could not come up with good explanations for why God allows this to happen. I joined friends for services at three different inner-city churches, and each time I heard the minister railing against the sins of homosexuals and the punishment of God in their affliction with AIDS. I left in disgust, because the vitriol conveyed in the sermon was incongruous with Jesus’ message of love and compassion.

A lot of water has flowed under the bridge between then and now. Living in the much smaller city of Ithaca, New York, I no longer look over my shoulder or cross to the other side of the street to stay safe. The glory of God‘s creation is not far away in our gorges, fields, and lakes.

The thing which has propelled me back to communion with others in our shared faith has been the burden I have carried as a caregiver for those afflicted by COVID and vaccine injury. The more I learn and the closer I come to the evil center of intentional actions which have led to the illness and death of so many people, the more fully I understand that I do not have the personal resources alone to handle this. The dissonance between those who see and those who don’t becomes more tense day to day. The houses of worship in which we would find comfort are often themselves places of denial, and pose a very real risk from shedding due to ongoing vaccination. Such is the case with my beloved Quakers.

Yet I have hope. “Did you realize that we have a Christian practice?” I recently said to my partner, Dr. Kory. The question made him squirm and his response made me laugh. Pierre is a deeply committed humanitarian and has the professional ethos to separate church and state. “People didn’t come to us for religious counseling,” he replied. “They came to us from medical care.”

Shit, I’m a Quaker. By my works, shall you know my faith. You couldn’t find me farther away from an inclination to evangelize. But the people who have held independent thoughts, resisted the onslaught, fought against our loss of liberty, and dedicated themselves to this work and to our patients are faithful Christians. In the 30 years that I have been in healthcare, I never before prayed with a patient until now. Funny how a genocide will change you. Yes, I have had patients ask to pray for me, and it has always been awkward. Last week one asked to pray for me and for the practice at the end of our visit. I easily accepted, and it lifts me still.

During the same visit, the patient told me about how he has struggled with his church’s inability to discuss the truth behind the virus and the jabs. As a result, he has stopped attending. Out loud he asked, “Where is God in all of this?” In this early morning hour, I am beginning to find an answer, which has been there all along but has a renewed vibrancy. God is in nature, God is in music, God is within each of us, God is in our loving relationships, God is in mercy, God is in tenacity, God is in renewed community. Praise God, from whom all blessings flow. Praise God, all creatures here below.

[ad_2]

Source link